From Zion- Great Song and Cover Performances: There are some songs that you don’t truly appreciate until another artist takes it on and makes it their own. Oftentimes the newer version draws out the original’s complexities in a way you never would have noticed before. Or maybe the first version is equally compelling, but the cover artist re imagined it with such grandeur . Follow Stephen Darori on Twitter, Linkedin and Facebook .

Saturday, April 29, 2017

Friday, April 28, 2017

Friday, April 21, 2017

Chuck Berry & Little Richard Bill Clinton’s Inauguration Ball’ HBO, USA,... with special lyrics for the occassion

Chuck Berry & Little Richard Bill Clinton’s Inauguration Ball’ HBO, USA, 19th January 1993

Reelin’ and Rockin’

Good Golly Miss Molly

Just let me hear some of that rock and roll music

Any old way you choose it

It's got a backbeat, you can't lose it

Any old time you use it

It's gotta be rock and roll music

If you wanna dance with me

If you wanna dance with me

I have no kick against modern jazz

Unless they try to play it too darn fast

And change the beauty of the melody

Until they sound just like a symphony

That's why I go for that rock and roll music

Any old way you choose it

It's got a backbeat, you can't lose it

Any old time you use it

It's gotta be rock and roll music

If you want to dance with me

If you want to dance with me

I took my loved one over cross the tracks

So she can hear my man a-wail a sax

I must admit they have a rockin' band

Man, they were blowin' like a hurricane

That's why I go for that rock and roll music

Any old way you choose it

It's got a backbeat, you can't lose it

Any old time you use it

It's gotta be rock and roll music

If you wanna dance with me

If you wanna dance with me

Way down South they gave a jubilee

The jokey folks, they had a jamboree

They're drinkin' homebrew from a wooden cup

The folks dancin' got all shook up

And started playin' that rock and roll music

Any old way you choose it

It's got a backbeat, you can't lose it

Any old time you use it

It's gotta be rock and roll music

If you wanna dance with me

If you wanna dance with me

Don't care to hear 'em play a tango

I'm in the mood to dig a mambo

It's way too early for a congo

So keep a-rockin' that piano

So I can hear some of that rock and roll music

Any old way you choose it

It's got a backbeat, you can't lose it

Any old time you use it

It's gotta be rock and roll music

If you wanna dance with me

If you wanna dance with me

Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

Chuck Berry poses for a portrait session in circa 1958 in Chicago.

“While no individual can be said to have invented rock and roll,” hedged the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame upon inducting Chuck Berry into its 1986 freshman class along with Elvis Presley, Little Richard, Jerry Lee Lewis, Buddy Holly, Fats Domino and others -- “Chuck Berry came the closest of any single figure to being the one who put all the essential pieces together.” And of course the hedge was justified in many ways, among them Presley’s preeminence and the equally momentous although not quite rock’n’roll innovations of classmates Ray Charles and James Brown.

But now that the man has died -- on March 18, unexpectedly, at 90 -- let’s get real. Chuck Berry did in fact invent rock’n’roll. Of course similar musics would have sprung up without him. Elvis was Elvis before he’d ever heard of Chuck Berry. Charles’ proto-soul vocals and Brown’s everything-is-a-drum were innovations as profound as Berry’s. Bo Diddley was a more accomplished guitarist. Doo-wop and New Orleans were moving right along. Et cetera. But none of those musics would have been as rich or seminal without him.

READ MORE

Details Emerge on Chuck Berry's Final Album 'CHUCK,' New Single 'Big Boys' Drops: Listen

After all, it was Chuck Berry who had the cultural ambition to sing as if the color of his skin wasn’t a thing -- mixing crystalline enunciation with a bad-boy timbre devoid of melisma and burr, he took aim at both the country fans he coveted and the white teenagers he saw coming. Nor did teen-targeted hits like “Rock and Roll Music,” “Sweet Little Sixteen” and “School Day” merely play to the kids Elvis had transformed into the biz’s next big market. With his instinct for the historical moment, alertness to the fads and folkways of his young fans, delight in an unprecedented American prosperity, matchless verbal facility and autobiographical recall, Berry played a major role in inventing teendom itself -- in augmenting its self-awareness and turning it into a subculture. And crucially, he established rock’n’roll as a songwriter’s medium. Some in his cohort wrote a fair amount, others barely at all. But it was Berry in particular who presaged Buddy Holly, the 1950s’ second great-songwriter-cum-great-performer. Between them they established the artistic template of ’60s rock, where self-written material was a prerequisite. And with the ’60s in the mix, consider Chuck Berry’s guitar.

Universal Pictures/ Everett Collection

Berry in the 1987 film Hail! Hail! Rock ’n’ Roll! with Johnnie Johnson (left) and Keith Richards.

Caveats again. Elvis fetishized an instrument that Scotty Moore could actually play, Carl Perkins was a master, and Bo Diddley -- never a major hitmaker but always a legend -- was a protean virtuoso. Each one imprinted himself on history, Bo especially. But Chuck Berry was the wellspring as a player and a showman. The two-stringed “Chuck Berry lick” was really many closely related licks. As critic Gregory Sandow once pointed out, different songs’ “fanfares” were distinct: “Maybellene”’s car horn, “School Day”’s school bell, “Too Much Monkey Business”’s jangling telephone, “Roll Over Beethoven”’s mini-solo. And though you can discern versions of that lick in recordings by both T-Bone Walker and Louis Jordan sideman Carl Hogan, it was Berry who had the gall and imagination to amp up such stray note clusters and forge a whole music out of them, integrating Ike Turner-style, guitar-based R&B and neater country-style picking into a new electric sound that changed the world’s ears. For the very different styles of George Harrison and Keith Richards -- of, you know, the Beatles and the Stones -- Berry’s guitar was foundational, and soon there wasn’t a rock guitarist anywhere who couldn’t play his shit. Contrary as always, Bob Dylan was more taken with his groove -- the rhythm of “Too Much Monkey Business,” he’s said, was where he got “Subterranean Homesick Blues.” Chuck Berry: inventor of rock’n’roll, lodestone of the “rock” rock’n’roll generated.

READ MORE

Little Richard on Chuck Berry's Death: 'I Lost One of My Best Friends In Music'

Yet though Charles Edward Anderson Berry got fairly rich remaking the world, which he always claimed was the main idea, he never became any kind of tycoon even though he was a famous skinflint who demanded cash payment before he’d join his pickup band onstage. And though he was key in establishing unalloyed democratic fun as rock’n’roll’s core value, he was too cantankerous a guy to leave his admirers feeling that he enjoyed his genius much. Born Oct. 18, 1926, which made this mythologist of teens the oldest of the rock’n’roll originals, he was raised in a lower-middle-class black St. Louis neighborhood by solid, hardworking, musical parents; one sister trained to be an opera singer. Chuck was also musical and hardworking -- he won a guitar competition in high school, married for life in 1948 and was supporting a family of four as of 1952. But his bad-boy voice wasn’t merely an act. An absurd crime spree involving a fake gun earned him the first of three prison bids in 1944, long before he and pianist Johnnie Johnson hit Chess Records in 1955.

Stephen J. Boitano/AP/REX/Shutterstock

Berry and wife Themetta at the Kennedy Center Honors in 2000.

Then ensued what the first of his uncountable greatest hits collections dubbed Chuck Berry’s golden decade. But “golden” is poetic license, and so is “decade.” Berry was a major star from 1955 to 1959 as well as a legendary concert draw throughout the high ’60s and long after. But note that although the three key teen anthems as well as the guitar hero foundation myth “Johnny B. Goode” all went pop top 10 in the ’50s (on what were then called the Best Sellers in Stores and Top 100 charts), not one reached No. 1, and Fats Domino and Little Richard never hit No. 1 either. Fact is, although Berry’s racial breakthroughs will always signify, his ’50s hits did somewhat better on the R&B chart, which also welcomed such canonical coups as “No Money Down” and the comic protest anthem “Too Much Monkey Business.” And in the Beatlemania-fueled 1964 comeback that followed his second prison term, the warmly pro-black but also pro-American “Promised Land,” a history of the Freedom Rides so subtle few figured it out at the time, didn’t make the top 40.

READ MORE

Chuck Berry's Guitarist Billy Peek Looks Back on 50 Years of Music and Friendship

The second prison term -- involving a 15-year-old girl he had reason to believe was older and always denied sleeping with, but with Chuck Berry you never know -- was a turning point. The first trial was transparently and disallowably racist, the second less obvious about it. But that doesn’t mean Berry was innocent, because he was always a very bad boy -- as in the 1986 autobiography replete with enticing blondes, written during the 1979 tax evasion prison term where all those cash payments caught up with him; or the 1989 lawsuit alleging that he’d set up peeping cameras in the ladies’ room of a restaurant he owned, which he escaped with a $1.5 million class action settlement plus a suspended sentence for marijuana possession. Or consider the Keith Richards-instigated 1987 Taylor Hackford documentary Hail! Hail! Rock ’n’ Roll, which, instead of turning into a publicity coup, Berry sabotaged by overamping his guitar and demanding extra cash upfront. Many stars age poorly, but the fairest guess here is that the theoretically post-racial Berry was deeply embittered by an American racism that remained in force -- and was also something like a predator perv.

READ MORE

Report: Chuck Berry Died of Natural Causes

Yet although Chuck Berry both missed out on and misused too much of the fun he transmuted into a core value, the art with which he achieved that transmutation was always playful -- sly sometimes, in fact often, but devoid of the meanness that marred his personal interactions. Plus, he was a funny guy. And for millions if not billions of people, that fun continues to inhere in music that remained indelible no matter how assiduously imitated. Its sheer musicality was irresistible. But Chuck Berry is loved first and foremost as a lyricist, and as a writer I second that emotion.

Dezo Hoffmann/REX/Shutterstock

Berry in 1965.

Under his own recognizance, with no say-so from anyone I’m aware of, Chuck Berry materially enriched a disreputable dialect of the English language that he clearly savored. Although he had no particular place to go and never ever learned to read or write so well, he took the message and he wrote it on the wall, and soon the folks dancing got all shook up. From irresistible words like “motorvating,” “coolerator” and “calaboose” to inevitable phrases like “any old way you choose it” and “campaign shouting like a Southern diplomat,” he was a master of the American demotic. Even after that second prison term threw him for a loop, he started back doing the things he used to do -- find the late diptych “Tulane”/“Have Mercy Judge.” It’s no wonder that very late in life he not only won Sweden’s Polar Music Prize but shared the first PEN songwriting award with Leonard Cohen.

Chuck Berry cut down hard on touring a decade ago. Yet when he turned 90 he announced that he’d soon go on the road to support his first new album in 38 years. It has long seemed passing strange that four of the teen heroes in the Hall of Fame’s freshman class -- Berry, Lewis, Domino and Little Richard -- were living long enough to be knocking on immortality’s door. One explanation is that their musical gifts were powered by a pitch of innate vitality known to few humans. So don’t forget that Chuck Berry has a new album coming out. It’s called Chuck.

Globe Photos/ZUMAPRESS.com

John Lennon, Berry and Yoko Ono on The Mike Douglas Show in 1972.

Watch Bruce Springfield 's having the thrill of his life. Chuck Berry With Bruce Springsteen & The E Street Band - Johnny B. Goode and How Chuck Berry Wrote “Johnny B. Goode” and Created the First Rock and Roll Guitar Hero

Deep down in Louisiana close to New Orleans

Way back up in the woods among the evergreens

There stood a log cabin made of earth and wood

Where lived a country boy named Johnny B. Goode

Who never ever learned to read or write so well

But he could play the guitar just like a ringin' a bell

Go go

Go Johnny go

Go

Go Johnny go

Go

Go Johnny go

Go

Go Johnny go

Go

Johnny B. Goode

He used to carry his guitar in a gunny sack

Go sit beneath the tree by the railroad track

Oh, the engineers would see him sittin' in the shade

Strummin' with the rhythm that the drivers made

The people passin' by they would stop and say

Oh my but that little country boy could play

Go go

Go Johnny go

Go

Go Johnny go

Go

Go Johnny go

Go

Go Johnny go

Go

Johnny B. Goode

His mother told him "Someday you will be a man,

And you will be the leader of a big old band.

Many people comin' from miles around

To hear you play your music when the sun go down

Maybe someday your name will be in lights

Saying Johnny B. Goode tonight."

Go go

Go Johnny go

Go go go Johnny go

Go go go Johnny go

Go go go Johnny go

Go

Johnny B. Goode

In 1954, at the age of 41, blues musician Muddy Waters had finally made it to the top. Or so it seemed.

“Hoochie Coochie Man” and “I Just Want to Make Love to You,” released that year, became his biggest sellers and remained in the Top 10 R&B charts for more than three months. But the winds of change were blowing, and that summer blues record sales suddenly plummeted, dropping by a dramatic 25 percent and sending shock waves through the Chicago music industry.

Record execs blamed the poor economy, but a fresh and more youth-oriented brand of music was starting to sweep the airwaves, one that was built on the bones of the very R&B, blues and country that they had so carefully nurtured. As Waters would later sing, “the blues had a baby and they named it rock and roll.”

In ’54, Elvis Presley paired the country tune “Blue Moon of Kentucky” with “That’s All Right,” a song originally performed by blues singer Arthur Crudup, and the single sold an impressive 20,000 copies. That same year, Bill Haley & His Comets sold millions with “Shake, Rattle and Roll” and “Rock Around the Clock.” In response, Leonard Chess of Chess Records sniffed out and signed two young electric guitar–playing rockers of his own. Bo Diddley and his rectangular guitar would become an enormous commercial success; but it was Chuck Berry’s crossover to the white teenage market that would make him a legend.

Charles Edward Anderson Berry, born to a middle-class family in St. Louis in 1926, was a brown-eyed charmer who loved the blues and poetry with almost equal fervor. After winning a high school talent contest with a guitar-and-vocal rendition of Jay McShann’s “Confessin’ the Blues,” he became serious about making music and started working the local East St. Louis club scene, where he put all of his skills to good use.

While Berry excelled at playing the blues of Muddy Waters and crooning in the suave manner of Nat King Cole, it was his ability to play “white music” that would eventually make him a star.

“The music played most around St. Louis was country-western and swing,” Berry said in his autobiography. “Curiosity provoked me to lay a lot of the country stuff on our predominantly black audience. After they laughed at me a few times, they began requesting the hillbilly stuff.” The sight and sound of a black man playing white hillbilly music, combined with Berry’s natural showmanship and his ability to improvise clever lyrics to fit any occasion, made him a top attraction with Missouri’s black community. But Berry had bigger aspirations; he wanted to make records.

While on a trip to Chicago he paid a 50-cent admission fee to see his favorite blues singer, Muddy Waters, perform, and after the show he worked his way toward the bandstand and managed a few words with his idol.

“It was the feeling I suppose one would get from having a word with the president or the pope,” Berry remembered. “I quickly told him of my admiration for his compositions and asked him who I could see about making a record.” Waters told the guitarist to see Leonard Chess. So, taking his hero at his word, Berry made a beeline for Chess Studios the next morning, introduced himself to the receptionist, and politely asked to see Chess. Remarkably, Chess waved him in, and Berry passionately delivered a well-rehearsed speech outlining his hopes as a musician.

“He had a look of amazement that he later told me was because of the businesslike way I talked to him,” Berry later said. Hearing Chuck’s homemade demo tape, the label president gravitated to a cover of “Ida Red,” a 1938 song made popular by country swing band Bob Wills and His Texas Playboys.

Chess recognized the crossover potential of a black artist playing country music, and he scheduled a session for May 21, 1955. After all, if a white man like Presley could make hit records by sounding black, why not try the reverse? During the session, Chess demanded a bigger sound for the song and added bass and maracas to Berry’s trio. He also told Berry to write new lyrics, insisting that “the kids want the big beat, cars and young love.”

Chuck quickly responded with an outrageous story about a man driving a V8 Ford, chasing his unfaithful girlfriend in her Cadillac Coupe de Ville. The title was changed from “Ida Red” to “Maybellene,” a name inspired by a brand of makeup teenage girls were wearing at the time. Although the record only made it to the mid-20s on the Billboard pop chart, its influence was massive in scope. Here was a black rock-and-roll record with across-the-board appeal, embraced by white teenagers and Southern hillbilly musicians alike (including Elvis Presley, who added it to his stage show). And it was fortunate for the electric guitar that one of its earliest champions was not only an extraordinary musician and showman, but also one of pop music’s greatest and most enduring singer-songwriters.

With monster hits such as “Roll Over Beethoven” (1956), “Rock and Roll Music” (1957), and “Sweet Little Sixteen” (1958), Chuck Berry did much to forge the genre. His formula was ingenious: write lethally funny lyrics about the teenage experience, strap them into a high-octane groove, add a little country twang, shake it up with a showstopping guitar solo, and then watch the acclaim pour in. It was a recipe that would dominate popular music for decades to come. And if early listeners didn’t understand how important his guitar was to the mix, Chuck soon made the connection explicit.

In his 1958 masterpiece “Johnny B. Goode,” Berry created the ultimate rock-and-roll folk hero in just a few snappy verses. As we all know, Goode wasn’t pounding a piano, singing into a microphone, or blowing a sax. In his choice of the electric guitar, something sleek and of the moment, the fictional character of Goode would forge an image of the archetypal rocker, doing as much to shape the history of the instrument as any real-life figure ever has. The song’s opening riff is a clarion call—perhaps the greatest intro in rock-and-roll history. It was played by Berry on an electric Gibson ES-350T, and it indeed sounded “just like a-ringin’ a bell.”

The tale begins “deep down in Louisiana,” where a country boy from a poor household is doing his best to get by. Johnny, we discover, “never ever learned to read or write so well,” but he has something better than a formal education or a diploma—he has talent, street smarts, and a guitar. Johnny’s Gibson is his instrument and also his ticket out of the backwoods. After introducing our hero, the anthem turns to his guitar. It’s portable—he could toss it into a “gunnysack” and practice anywhere, even beneath the trees by the railroad. It’s astonishingly loud. More powerful than a passing locomotive, Johnny’s soaring notes stop train passengers dead in their tracks.

By the last verse, the guitarist’s reputation has spread far and wide. As his growing legion of fans and supporters cheer him on with shouts of “Go, Johnny, Go,” even his long-suffering mother is forced to concede “maybe someday your name will be in lights.” “Johnny B. Goode” is a brilliant, uniquely American rags-to-riches story, but with a modern twist. Where Horatio Alger’s nineteenth-century heroes rose from humble backgrounds to lives of middle-class security through hard work and virtue, Goode excelled on his own terms; he was uneducated, solitary. He was a bad boy, a story line all the more compelling to a generation of teenagers just beginning to identify with outsider icons such as James Dean and Elvis Presley. It was a song that thrilled and exhilarated audiences both black and white.

It became a massive crossover hit, peaking at Number 2 on Billboard magazine’s Hot R&B Sides chart and Number 8 on the Billboard Hot 100. To teenage ears, Chuck’s guitar signaled the dawn of a new era. The glorious peal of his 350T proclaimed that school was out. John Lennon, Bob Dylan, Jimi Hendrix, Keith Richards and Bruce Springsteen were just a few of the working-class kids who immediately grasped the sly moral of the song, and who recognized a good blueprint when they saw one.

“I could never overstress how important [Berry] was in my development,” said Richards, perhaps the ultimate rock-and-roll outlaw. Reflecting on the significance of “Johnny B. Goode” and his other hits, Berry later played down his originality. He was attempting to marry the diction of Nat King Cole, the lyrics of Louis Jordan, and the swing of jazz guitarist Charlie Christian, but with the soul of Muddy Waters. “Ain’t nothin’ new under the sun,” he was fond of saying. But he was being modest. His synthesis of genres and his use of amplification were wholly original.

If Christian introduced the electric guitar to a mass audience, Berry created its grandest mythology. As the electric guitar began to take on its signature shape in the Fifties—almost indistinguishable from the guitars of today—it bears noting how conspicuously sexy that design had become. With curves that cartoonishly mimicked the lines of a woman’s hips, and an undeniably phallic neck, the guitar may have preceded the sexual revolution of the Sixties, but it would become a perfect visual complement to it. Its provocative design was something Berry was one of the first to acknowledge, and that he rarely failed to exploit in his live shows.

While he had to be careful with how far he went—Chuck was one of the first black crossover rock-and-roll artists in a very racially charged time—he wasn’t that careful. He often played to predominately white audiences at rock-and-roll stage shows booked by DJ/promoter Alan Freed, or in Hollywood films such as Rock, Rock, Rock!, Go, Johnny Go! and Mister Rock and Roll. During each appearance, Berry would kiss his Gibson or Gretsch on the neck, wrestling with it as he made it scream and swoon during his wild solos, jutting it lasciviously from his waist as he did splits. The Gibson ES-350T was particularly well suited to Berry’s gyrations. In the mid Fifties, electric guitar players had two choices: either a full hollow-body or a compact solid-body. Gibson had been receiving requests from players for something in-between the two styles, so in 1955 their first “thinline” electrics were developed.

The guitar’s medium build was a perfect fit for Chuck’s high-energy stage presentation. Chuck’s guitar antics and wild gyrations were provocative stuff for suburban kids, who were used to gently swaying crooners such as Frank Sinatra or Rosemary Clooney. And while they might not have understood all the implications of his act, one thing was clear: the electric guitar presented a seriously dangerous, sexy alternative to the comparatively staid piano or the sax. At the end of the Fifties, dozens of guitar-playing Johnny B. Goodes appeared, irrevocably changing the musical landscape, all playing in small electric combos resembling those pioneered by Chuck Berry and Muddy Waters.

As for Waters, he had a few more hits, including “Mannish Boy” in 1956 and “She’s Nineteen Years Old” in 1958. But the music of a 40-something guitarist like Muddy was being overtaken by rock and roll, driving him back into the small blues joints from whence he came. As Waters ruefully noted, “[Blues] is not the music of today; it’s the music of yesterday.” Little did he suspect that a few short years later, his music (along with that of younger acts such as Berry and Elvis) would find new life across the Atlantic, where it would be discovered by and inspire a generation of white British teens.

They would go on to pick up electric guitars and start blues and rock bands of their own. The Rolling Stones (who borrowed their name from a Waters song), the Animals, the Yardbirds, Cream and Led Zeppelin would pay homage—not to mention royalties—to those pioneers. Blues played on electric guitars, it turned out, was far from the music of yesterday. Indeed, it would be the music of today for decades to come.

Thursday, April 20, 2017

The Rolling Stones - Angie - OFFICIAL PROMO (Version 1)

Angie, Angie

When will those dark clouds all disappear

Angie, Angie

Where will it lead us from here

With no lovin' in our souls

And no money in our coats

You can't say we're satisfied

Angie, Angie

You can't say we never tried

Angie, you're beautiful

But ain't it time we say goodbye

Angie, I still love you

Remember all those nights we cried

All the dreams were held so close

Seemed to all go up in smoke

Let me whisper in your ear

Angie, Angie

Where will it lead us from here

Oh, Angie, don't you wish

Oh your kisses still taste sweet

I hate that sadness in your eyes

But Angie

Angie

Ain't it time we said goodbye

With no lovin' in our souls

And no money in our coats

You can't say we're satisfied

Angie, I still love you baby

Everywhere I look I see your eyes

There ain't a woman that comes close to you

Come on baby dry your eyes

Angie, Angie ain't good to be alive

Angie, Angie, we can't say we never tried

The big rumor about this song is that it was written about David Bowie's wife, Angela, who wrote in her autobiography that she once walked in on Bowie and Mick Jagger in bed together - a story Jagger denies. According to the rumor, Jagger wrote this song to appease her, but it was Jagger's bandmate Keith Richards who wrote most of the song. Jagger had this to say about it: "People began to say that song was written about David Bowie's wife but the truth is that Keith wrote the title. He said, 'Angie,' and I think it was to do with his daughter. She's called Angela. And then I just wrote the rest of it."

.

There was also speculation that Richards' girlfriend Anita Pallenberg inspired this song, but Keith cleared it up in his 2010 autobiography Life, where he wrote: "While I was in the [Vevey drug] clinic (in March-April 1972), Anita was down the road having our daughter, Angela. Once I came out of the usual trauma, I had a guitar with me and I wrote 'Angie' in an afternoon, sitting in bed, because I could finally move my fingers and put them in the right place again, and I didn't feel like I had to s--t the bed or climb the walls or feel manic anymore. I just went, 'Angie, Angie.' It was not about any particular person; it was a name, like ohhh, Diana. I didn't know Angela was going to be called Angela when I wrote 'Angie.' In those days you didn't know what sex the thing was going to be until it popped out."

.

A rare ballad for The Stones, this was the first single released from Goat's Head Soup. It wasn't typical of their sound, since most of the band's material at the time was hard and aggressive. Still, it was a huge hit, and their only ballad that hit #1 in the US.

.

This is one of the few Rolling Stones songs that is acoustic.

.

Keith Richards wrote this song in Switzerland after the Exile on Main St. album had been approved by the record company, but before it was released. "Angie" was one of the first songs The Stones recorded for Goat's Head Soup, which they first attempted in Jamaica at the Dynamic Sounds studio in Kingston. They got very little done at these sessions, arriving nightly with armed escort and locking the doors until they were done for the day. Much of the album was done at sessions in Los Angeles and London under more hospitable conditions.

.

The Angela Bowie rumor picked up steam in 1990, when she went on The Joan Rivers Show and claimed she once walked in on David Bowie and Mick Jagger in bed together naked. What's even more shocking is that Rivers had her own talk show. She was quickly replaced by Arsenio Hall.

.

Nicky Hopkins played piano on this track. He became part of the band's inner circle after working on the 1966 Stones album Between The Buttons.

.

In 2005 German chancellor Angela Merkel appropriated this acoustic ballad for her Christian Democratic Union Party. "We're surprised that permission wasn't requested," said a Stones spokesman of Merkel's choice of song. "If it had been, we would have said no."

.

The line from this song, "Ain't it time we said goodbye," was used as the title to Robert Greenfield's 2014 book, which chronicles his time covering the Stones' 1971 British tour and their Exile on Main St. sessions for Rolling Stone magazine. Greenfield is not a fan of the song, however, calling it "soppy and far too sweet for my taste."

Tuesday, April 18, 2017

Jimmie Rodgers - English Country Garden

How many gentle flowers grow in an English country garden?

I'll tell you now, of some that I know, and those I miss I hope you'll pardon.

Daffodils, hearts-ease and flocks, meadow sweet and lilies, stocks,

Gentle lupins and tall hollyhocks,

Roses, fox-gloves, snowdrops, forget-me-knots in an English country garden.

I'll tell you now, of some that I know, and those I miss I hope you'll pardon.

Daffodils, hearts-ease and flocks, meadow sweet and lilies, stocks,

Gentle lupins and tall hollyhocks,

Roses, fox-gloves, snowdrops, forget-me-knots in an English country garden.

How many insects find their home in an English country garden?

I'll tell you now of some that I know, and those I miss, I hope you'll pardon.

Dragonflies, moths and bees, spiders falling from the trees,

Butterflies sway in the mild gentle breeze.

There are hedgehogs that roam and little garden gnomes in an English country garden.

I'll tell you now of some that I know, and those I miss, I hope you'll pardon.

Dragonflies, moths and bees, spiders falling from the trees,

Butterflies sway in the mild gentle breeze.

There are hedgehogs that roam and little garden gnomes in an English country garden.

How many song-birds make their nest in an English country garden?

I'll tell you now of some that I know, and those I miss, I hope you'll pardon.

Babbling, coo-cooing doves, robins and the warbling thrush,

Blue birds, lark, finch and nightingale.

We all smile in the spring when the birds all start to sing in an English country garden.

I'll tell you now of some that I know, and those I miss, I hope you'll pardon.

Babbling, coo-cooing doves, robins and the warbling thrush,

Blue birds, lark, finch and nightingale.

We all smile in the spring when the birds all start to sing in an English country garden.

Sunday, April 16, 2017

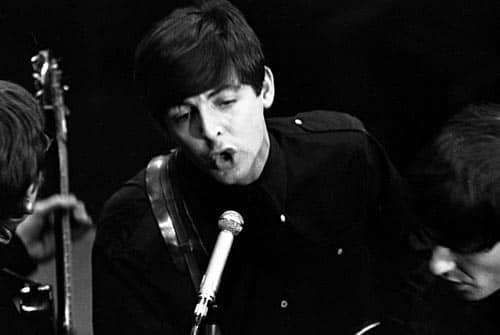

Sir Paul McCartney's career was celebrated by some of rock's biggest names as part of the 33rd annual Kennedy Center Honors. Macca was recognized alongside TV giant Oprah Winfrey, country legend Merle Haggard and others by President Obama at the event. McCartney was treated to a rendition of 'Hello, Goodbye' by No Doubt and a duet of 'Maybe I'm Amazed' by Foo Fighters front-man Dave Grohl and pop singer Norah Jones. Later, Aerosmith's Steven Tyler, who was asked to perform by McCartney, did a medley of songs from 'Abbey Road.' James Taylor and Mavis Staples closed out the show with 'Let It Be' and 'Hey Jude.'

Let It Be

When I find myself in times of trouble

Mother Mary comes to me

Speaking words of wisdom, let it be

And in my hour of darkness

She is standing right in front of me

Speaking words of wisdom, let it be

Oh, let it be, let it be, let it be, let it be

Whisper words of wisdom, let it be

And when the broken hearted people

Living in the world agree

There will be an answer, let it be

For though they may be parted

There is still a chance that they will see

There will be an answer, let it be

Oh, let it be, let it be, let it be, let it be

And there will be an answer, let it be

Oh, let it be, let it be, let it be, let it be

Whisper words of wisdom, let it be

Oh, let it be, let it be, let it be, let it be

Whisper words of wisdom, let it be

And when the night is cloudy

There…

Paul McCartney was a singer and multi-instrumentalist in The Beatles. Alongside John Lennon, he was half of one of the world's most successful songwriting teams in history.

Paul was one of the most innovative bass players that ever played bass, and half the stuff that's going on now is directly ripped off from his Beatles period. He was coy about his bass playing. He's an egomaniac about everything else, but his bass playing he was always a bit coy about. He is a great musician who plays the bass like few other people could play it.

John Lennon, 1980

All We Are Saying, David Sheff

All We Are Saying, David Sheff

The early years

James Paul McCartney was born in Liverpool's Walton Hospital on 18 June 1942. His father Jim worked in the cotton trade and played trumpet and piano in jazz and ragtime bands, and his mother Mary worked as a midwife.

Paul attended the Stockton Wood Road primary school, then went on to the Joseph Williams junior school before passing his 11 Plus in 1953 and gaining a place at the Liverpool Institute.

The following year, while travelling on a bus to the Institute, he met George Harrison, who was also a student there.

In 1955 the McCartneys moved to 20 Forthlin Road, a council house in the Allerton district of Liverpool. It cost them one pound and six shillings a week to live there. The house was bought by the National Trust in 1995, and today is a popular tourist destination. Back then, though, it was an unassuming terraced house built by the local authority in the 1920s.

On 31 October 1956, Mary McCartney died of an embolism following a mastectomy. She was a heavy smoker who had been suffering from breast cancer. The death shook the McCartney family, and later led to a bond between Paul and John Lennon, who lost his mother in 1958.

Jim McCartney was a keen musician who had been leader of Jim Mac's Jazz Band in the 1920s. There was an upright piano in the front room at 20 Forthlin Road, which Jim bought from Harry Epstein's NEMS store, which Beatles manager Brian Epstein would later take over.

Jim encouraged Paul and his brother Mike to be musical, and gave Paul a trumpet following the death of his mother. When skiffle became a national craze, however, Paul swapped the instrument for a £15 Framus Zenith acoustic guitar.

Being left-handed, Paul initially had trouble playing the instrument. He later learned to restring it, and wrote his first song, I Lost My Little Girl. He took music lessons for a while, but preferred instead to learn by ear. Paul also began playing piano, and wrote When I'm Sixty-Four while still living at Forthlin Road.

Paul McCartney met John Lennon at the Woolton fete on 6 July 1957, between performances by The Quarrymen. They became friends and began writing and performing songs together. McCartney later persuaded Lennon to allow George Harrison into the band as lead guitarist in 1958.

With The Beatles

The Beatles, as they became, gradually grew in popularity after performing many times in and around Liverpool and Hamburg, Germany. After Stuart Sutcliffe left the band, McCartney reluctantly took over his role as bass guitarist. He later bought a left-handed 1962 Hofner bass, which became part of The Beatles' iconography during the 1960s.

After The Beatles signed to Parlophone in 1962 and began releasing records, the songwriting partnership of Lennon-McCartney became celebrated. As well as penning the bulk of the band's recorded output, they also wrote for artists including Cilla Black, Billy J Kramer and Peter and Gordon.

As they became a worldwide phenomenon The Beatles relocated from Liverpool to London, but Lennon, Harrison and Ringo Starr eventually moved away from the city. McCartney, however, remained in central London, enjoying the various artistic and cultural benefits of the capital. He lived for some years at 7 Cavendish Avenue in St John's Wood, near to EMI's Abbey Road Studios.

In the mid 1960s McCartney became interested in experimental music, and made tape loops and avant-garde recordings, both with The Beatles and alone. The first to take on a non-Beatles musical commitment, in 1966 McCartney wrote the score for the film The Family Way. It later won an Ivor Novello award for Best Instrumental Theme.

By this time The Beatles had long since tired of touring, having become unable to hear their own voices and instruments above the screams of the audience. McCartney reluctantly agreed to the other members' wishes to stop touring, which they did in August 1966.

When Brian Epstein died in 1967, McCartney made efforts to keep the group together. He effectively led the making of the Magical Mystery Tour film and album, and in 1969 tried to persuade the group to take to the stage once more. Lennon's response was: "I think you're mad."

However, they did play the celebrated rooftop gig on the top of Apple's offices, filmed as part of the Let It Be project. McCartney led the group through their final recorded album, Abbey Road, released prior to Let It Be in 1969.

He was unhappy with Phil Spector's production on the Let It Be album. He also favoured Lee Eastman, father of Paul's wife Linda, when the group were looking for a new manager in 1969. Instead they appointed Allen Klein, a move bitterly contested by McCartney.

He was unhappy with Phil Spector's production on the Let It Be album. He also favoured Lee Eastman, father of Paul's wife Linda, when the group were looking for a new manager in 1969. Instead they appointed Allen Klein, a move bitterly contested by McCartney.

Although John Lennon left The Beatles in September 1969, McCartney persuaded him to keep it from the press. Instead, McCartney himself announced the band's break-up on 10 April 1970, during promotion for his first solo album McCartney. The Beatles' legal partnership was dissolved following a lawsuit filed by McCartney in December 1970.

The solo years

As with all the former members of The Beatles, McCartney's solo output was varied, yet also variable in quality - for every Band On The Run it seemed like there was a Frog Chorus. In August 1971 he formed Wings, and in 1977 released Mull Of Kintyre, which remained the UK's highest selling single until 1984. In the 1980s he collaborated with Elvis Costello, and in 1991 released his first classical work, the Liverpool Oratorio. Since then he has released a wide range of albums in a variety of styles, and has undertaken a number of world tours.

John Lennon's death in December 1980 led to a media frenzy. Asked how he felt, McCartney was reported as describing it as "a drag". He was pilloried for the comments, and later expressed regret, saying he had been at a loss for words. He later revealed that he had cried all evening in reaction to the news.

John Lennon's death in December 1980 led to a media frenzy. Asked how he felt, McCartney was reported as describing it as "a drag". He was pilloried for the comments, and later expressed regret, saying he had been at a loss for words. He later revealed that he had cried all evening in reaction to the news.

McCartney retired from live performances for a time following the death of John Lennon in 1980, although in subsequent years he returned to the stage for a series of world tours. Wings disbanded in 1981, the same year that he, Ringo Starr and George Harrison sang together on the latter's All Those Years Ago, a tribute to Lennon.

From 1976 McCartney began playing Beatles songs again, after years of refusing to. In the 1990s he reunited with Harrison and Starr to work on the Anthology project, and added instrumentation and vocals to two Lennon demos, Free As A Bird and Real Love.

Today Paul McCartney holds the record of being the most successful musician and composer in pop music history.

Friday, April 7, 2017

Joan Baez Live at Woodstock-Joe Hill-Swing low sweet cheriot Vara broadc...

Joan Baez, Paul Robeson: Joe Hill

SONG Joe Hill

SONG Joe Hill

SONGWRITERS Alfred Hayes (words) and Earl Robinson (music)

PERFORMERS Joan Baez, Paul Robeson, others

APPEARS ON From Every Stage, Woodstock: Music From The Original Soundtrack and More (Baez); Live at Carnegie Hall (Robeson)

Although popularized by Joan Baez' performance in the 1970 film Woodstock, this labor ballad traces its pedigree back to a 1930 poem by the British writer Alfred Hayes called "I Dreamed I Saw Joe Hill Last Night." (Some accounts have Hayes writing the poem in 1925.) In 1936, Seattle composer Earl Robinson set the poem to music; since then, various artists have performed the song as an inspiration for organizing labor and other community movements. In addition to Baez, singers of Joe Hill include Paul Robeson, Pete Seeger and Phil Ochs. In 1958, Robeson performed what must have been the definitive version for an earlier generation at his Carnegie Hall concert. "Joe Hill" remains a staple of Baez' concerts to this day.

The song's unlikely subject was born Joel Emmanuel Hagglund in Sweden sometime between 1879 and 1882. Hagglun emigrated to the United States in 1902 and began traveling the American west as a migrant laborer. Somewhere along the line, Hagglund became known as Joseph Hillstrom, a name perhaps inevitably shortened to Joe Hill. Hill joined the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW, also known as the "Wobblies") in 1910, gaining prominence as an organizer and writer of labor songs.

In early 1914, Hill arrived in Park City, Utah, having found work there as a silver miner. Shortly after Hill's arrival in Park City, masked robbers murdered a Salt Lake City butcher and his son in the family shop. During the robbery, the butcher returned fire and wounded one of the robbers. Shortly after, Hill appeared in at local doctor's office with a bullet wound. Although he denied robbing the butcher -- and rudimentary forensic evidence supported his claim -- Hill was nonetheless arrested and tried for murder. Hill's efforts to keep the IWW out of his trial failed, and it is thought today that his membership in the radical labor organization was the key factor in the guilty verdict brought against him. A Utah firing squad executed Hill on November 19, 1915. (Complete Wikipedia article here.)

Shortly before his death, Hill sent the following message to IWW leader Bill Haywood:

Goodbye Bill. I die like a true blue rebel. Don't waste any time in mourning. Organize... Could you arrange to have my body hauled to the state line to be buried? I don't want to be found dead in Utah.

"Joe Hill" has been performed around the world in over a dozen languages. Of the two versions presented here, Baez' version shows "Joe Hill" in its folk roots and -- through Robeson's more classically oriented rendition -- the extent to which the song has been adapted. Earl Robinson had this to say about "Joe Hill":

"Joe Hill" was written in Camp Unity in the summer of 1936 in New York State, for a campfire program celebrating him and his songs, "Casey Jones," "Pie in the Sky" and others. Before the end of that summer we were hearing of performances in a New Orleans Labor Council, a San Francisco picket line, and it was taken to Spain by the members of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade to help in the fight against Franco. It has travelled around the world since like a folk song, been translated into twelve or fifteen languages. Joan Baez' singing of the song at Woodstock brought it to popular attention, but I still get asked the question, "Did you write 'Joe Hill'?" [More here and here.]

LYRICS

I dreamed I saw Joe Hill last night,

alive as you and me.

Says I "But Joe, you're ten years dead"

"I never died" said he,

"I never died" said he.

"The Copper Bosses killed you Joe,

they shot you Joe" says I.

"Takes more than guns to kill a man"

Says Joe "I didn't die"

Says Joe "I didn't die"

"In Salt Lake City, Joe," says I,

Him standing by my bed,

"They framed you on a murder charge,"

Says Joe, "But I ain't dead,"

Says Joe, "But I ain't dead."

And standing there as big as life

and smiling with his eyes.

Says Joe "What they can never kill

went on to organize,

went on to organize"

From San Diego up to Maine,

in every mine and mill,

Where working men defend their rights,

it's there you find Joe Hill,

it's there you find Joe Hill!

I dreamed I saw Joe Hill last night,

alive as you and me.

Says I "But Joe, you're ten years dead"

"I never died" said he,

"I never died" said he.

SONG Joe Hill

SONG Joe Hill

SONGWRITERS Alfred Hayes (words) and Earl Robinson (music)

PERFORMERS Joan Baez, Paul Robeson, others

PERFORMERS Joan Baez, Paul Robeson, others

APPEARS ON From Every Stage, Woodstock: Music From The Original Soundtrack and More (Baez); Live at Carnegie Hall (Robeson)

Although popularized by Joan Baez' performance in the 1970 film Woodstock, this labor ballad traces its pedigree back to a 1930 poem by the British writer Alfred Hayes called "I Dreamed I Saw Joe Hill Last Night." (Some accounts have Hayes writing the poem in 1925.) In 1936, Seattle composer Earl Robinson set the poem to music; since then, various artists have performed the song as an inspiration for organizing labor and other community movements. In addition to Baez, singers of Joe Hill include Paul Robeson, Pete Seeger and Phil Ochs. In 1958, Robeson performed what must have been the definitive version for an earlier generation at his Carnegie Hall concert. "Joe Hill" remains a staple of Baez' concerts to this day.

The song's unlikely subject was born Joel Emmanuel Hagglund in Sweden sometime between 1879 and 1882. Hagglun emigrated to the United States in 1902 and began traveling the American west as a migrant laborer. Somewhere along the line, Hagglund became known as Joseph Hillstrom, a name perhaps inevitably shortened to Joe Hill. Hill joined the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW, also known as the "Wobblies") in 1910, gaining prominence as an organizer and writer of labor songs.

In early 1914, Hill arrived in Park City, Utah, having found work there as a silver miner. Shortly after Hill's arrival in Park City, masked robbers murdered a Salt Lake City butcher and his son in the family shop. During the robbery, the butcher returned fire and wounded one of the robbers. Shortly after, Hill appeared in at local doctor's office with a bullet wound. Although he denied robbing the butcher -- and rudimentary forensic evidence supported his claim -- Hill was nonetheless arrested and tried for murder. Hill's efforts to keep the IWW out of his trial failed, and it is thought today that his membership in the radical labor organization was the key factor in the guilty verdict brought against him. A Utah firing squad executed Hill on November 19, 1915. (Complete Wikipedia article here.)

Shortly before his death, Hill sent the following message to IWW leader Bill Haywood:

Goodbye Bill. I die like a true blue rebel. Don't waste any time in mourning. Organize... Could you arrange to have my body hauled to the state line to be buried? I don't want to be found dead in Utah.

"Joe Hill" has been performed around the world in over a dozen languages. Of the two versions presented here, Baez' version shows "Joe Hill" in its folk roots and -- through Robeson's more classically oriented rendition -- the extent to which the song has been adapted. Earl Robinson had this to say about "Joe Hill":

"Joe Hill" was written in Camp Unity in the summer of 1936 in New York State, for a campfire program celebrating him and his songs, "Casey Jones," "Pie in the Sky" and others. Before the end of that summer we were hearing of performances in a New Orleans Labor Council, a San Francisco picket line, and it was taken to Spain by the members of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade to help in the fight against Franco. It has travelled around the world since like a folk song, been translated into twelve or fifteen languages. Joan Baez' singing of the song at Woodstock brought it to popular attention, but I still get asked the question, "Did you write 'Joe Hill'?" [More here and here.]

LYRICS

I dreamed I saw Joe Hill last night,

alive as you and me.

Says I "But Joe, you're ten years dead"

"I never died" said he,

"I never died" said he.

"The Copper Bosses killed you Joe,

they shot you Joe" says I.

"Takes more than guns to kill a man"

Says Joe "I didn't die"

Says Joe "I didn't die"

"In Salt Lake City, Joe," says I,

Him standing by my bed,

"They framed you on a murder charge,"

Says Joe, "But I ain't dead,"

Says Joe, "But I ain't dead."

And standing there as big as life

and smiling with his eyes.

Says Joe "What they can never kill

went on to organize,

went on to organize"

From San Diego up to Maine,

in every mine and mill,

Where working men defend their rights,

it's there you find Joe Hill,

it's there you find Joe Hill!

I dreamed I saw Joe Hill last night,

alive as you and me.

Says I "But Joe, you're ten years dead"

"I never died" said he,

"I never died" said he.

I dreamed I saw Joe Hill last night,

alive as you and me.

Says I "But Joe, you're ten years dead"

"I never died" said he,

"I never died" said he.

"The Copper Bosses killed you Joe,

they shot you Joe" says I.

"Takes more than guns to kill a man"

Says Joe "I didn't die"

Says Joe "I didn't die"

"In Salt Lake City, Joe," says I,

Him standing by my bed,

"They framed you on a murder charge,"

Says Joe, "But I ain't dead,"

Says Joe, "But I ain't dead."

And standing there as big as life

and smiling with his eyes.

Says Joe "What they can never kill

went on to organize,

went on to organize"

From San Diego up to Maine,

in every mine and mill,

Where working men defend their rights,

it's there you find Joe Hill,

it's there you find Joe Hill!

I dreamed I saw Joe Hill last night,

alive as you and me.

Says I "But Joe, you're ten years dead"

"I never died" said he,

"I never died" said he.

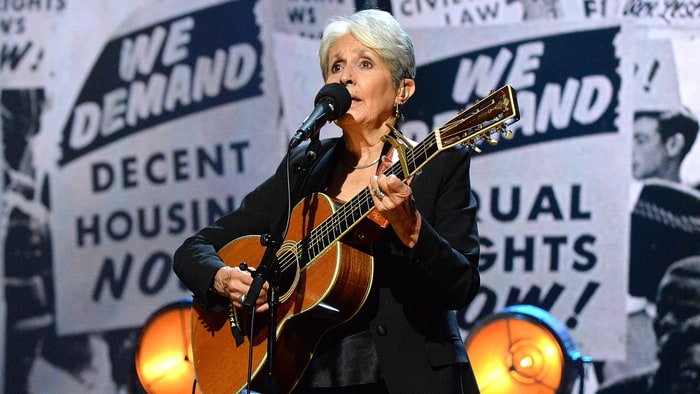

Joan Baez Performs Thrilling 'Swing Low, Sweet Chariot' at Rock Hall of Fame

Baez also revisited songs from The Band, Woody Guthrie with Mary Chapin Carpenter, Indigo Girls

Joan Baez played with Mary Chapin Carpenter and the Indigo Girls at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction ceremony. Kevin Mazur/WireImage/Getty

Joan Baez played with Mary Chapin Carpenter and the Indigo Girls at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction ceremony. Kevin Mazur/WireImage/Getty

Joan Baez delivered spare, captivating versions of three songs from her repertoire on Friday night at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction ceremony at Brooklyn's Barclays Center.

RELATED

Joan Baez's Fighting Side: The Life and Times of a Secret Badass

The Sixties icon helped invent the idea of the protest singer – more than five decades later, she's still at it

Baez initially took the stage alone to perform a rendition of "Swing Low, Sweet Chariot," a traditional number that she also performed at Woodstock in 1969. "My voice is my greatest gift," Baez said during her induction speech, and the solo format allowed her to demonstrate that gift's extraordinary range.

She played a bare outline of melody on guitar, but the focus was entirely on her singing: she transformed single words like "home" and "chariot" into multi-note, virtuosic displays. She also adjusted the song's lyrics in the final line – "Coming for to carry me home" – to include President Trump, suggesting that even he was not beyond saving.

After "Swing Low, Sweet Chariot," Baez invited singer/songwriter Mary Chapin Carpenter and the Indigo Girls to join her onstage. Together, the quartet tackled "Deportee (Plane Wreck At Los Gatos)," a protest tune written by Woody Guthrie, and "The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down," one of the Band's most popular songs.

"Deportee" was a serene affair, full of dulcet strums and graceful singing from all four artists. Baez picked up the tempo during "The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down" and enjoyed slipping in front of the beat and waiting for it catch up. A few members of the crowd joined in during the song's famous, hummable chorus.

Baez initially expressed surprise when she found out about her Rock Hall induction. "I never considered myself to be a rock and roll artist," she explained in a statement. "But as part of the folk music boom which contributed to and influenced the rock revolution of the Sixties, I am proud that some of the songs I sang made their way into the rock lexicon. I very much appreciate this honor and acknowledgement by the Hall of Fame."

Early in her career, Baez recorded traditional songs like "House of the Rising Sun," which later became a major hit for The Animals, and "John Riley," which subsequently influenced the Byrds' rendition on 1966's Fifth Dimension. Baez also performed at Woodstock, one of rock's seminal events.

Even if her music leans more towards folk, longtime friend Bob Neuwirth suggested that Baez's spirit makes her a natural candidate for the Rock Hall. "Joan has that rock and roll attitude toward life and freedom and love," Neuwirth said recently. "She has a kind of bravery that could just kick down the doors."

Baez's Hall of Fame induction is the latest acknowledgement of her contributions to popular music. She earned a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Grammys in 2007.

She is currently at work on a new album produced by Joe Henry. "So many people have said to me, out of the blue, 'We need Joan Baez right now,'" Henry told Rolling Stone. "She's been fiercely standing where she is her whole life."

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)